What’s the last literary event you participated in? Recently, my Instagram was flooded with readers lining up for the latest book by Rebecca Yarros, Onyx Storm. I’ll confess to being a total newbie to the world of romantasy, but it was exciting to see dispatches from some of my favorite indie bookstores (shout out to Quail Ridge Books in my hometown of Raleigh, NC) having huge launch events for the book.

The most recent literary event I participated in was for the last Harry Potter book. I first read the books just after Book 4 was released, so I have strong memories of the midnight drops of books 5, 6, and 7. Book 5 came out the summer after I’d finished studying in London, and so a group of friends and my sister and I got our copies from the aforementioned Quail Ridge in Raleigh. For Book 6, I was living in London again, and I got my copy with my equally obsessed roommate Kaitlin from heavenly Foyles a full five hours before my American friends. And for Book 7, I was living in Bethesda, MD, and picked up my copy from the local Barnes and Noble with the guy I’d just made read all six previous books (who’s now my husband). Events spurn memories; those memories last, sometimes, even longer than your memories of the reason for the event. (This is especially true for me for the HP series—books that were hugely important to me for a long time that I barely think of now, mostly because of the actions of their increasingly horrible author, She Who Must Not Be Named.)

I was thinking about the literary event when I finally got around to reading Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo last month. I say “finally” because it felt like, when the book was published last September, everybody who was anybody read it immediately. That was the impression I got from Twitter and social media, anyway. And certainly the hype machine was in full swing. Sarah Jessica Parker was papped with an advanced copy. In the UK, Rooney’s publisher Faber planned the biggest trade campaign ever around Intermezzo’s release, and the US enjoyed 140+ bookstore events. There were notepads! exclusive dust jackets! window installations! bandannas! Baggu bags! So. Much. Swag.

Seeing this much attention paid to a book is awesome! Book swag is awesome! (I got a free t-shirt with my copy of Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun that I love to this day.) (And I never actually finished reading Klara and the Sun. Oh dear.) But if you’re an author who isn’t Sally Rooney or Sarah J. Maas or Colleen Hoover or Dan Brown or Richard Osman—there was just a job listing posted by Penguin Random House UK looking for someone to manage his campaigns, and only his campaigns—which is 99% of authors, then you might feel a bit put out that all this money and effort is put behind some writers, a very few, really, while others are left to essentially pay for their own marketing campaigns.

The business of traditional publishing is not what interests me here, though that’s certainly fascinating.1 What interests me is how the Literary Event can make you, the reader, feel like a book’s moment has already come and gone, and how our hot take culture can make you feel like you’re always late to the party. (I’ve written about hot take critical culture in relation to popular music already—shoutout to Cowboy Carter for taking home the Grammy for best country album!) The urge to buy a popular book, read it quickly, and Have an Opinion about it is strong. But that’s not how art works; that’s not how art means.

And Intermezzo is a book that demands slow reading. It’s got an epigraph by Wittgenstein, for God’s sake! And a whole appendix at the back of the book cataloging its numerous literary references. It’s got chess on the cover, and chess inside, too! The point-of-view is purposely dense and breathless; the paragraphs are very long. There are still, as in all previous Rooney books and a shocking number of novels by Irish authors, NO QUOTATION MARKS. It’s a book, like the best books, that benefits from long simmering in the mind of its reader—maybe even a few days in the fridge for the flavors to really come together. It’s Rooney’s most ambitious book, and maybe her most sincere one. It’s a book I’m still thinking about, which is how it should be. Even if it feels like the rest of the world has moved on.

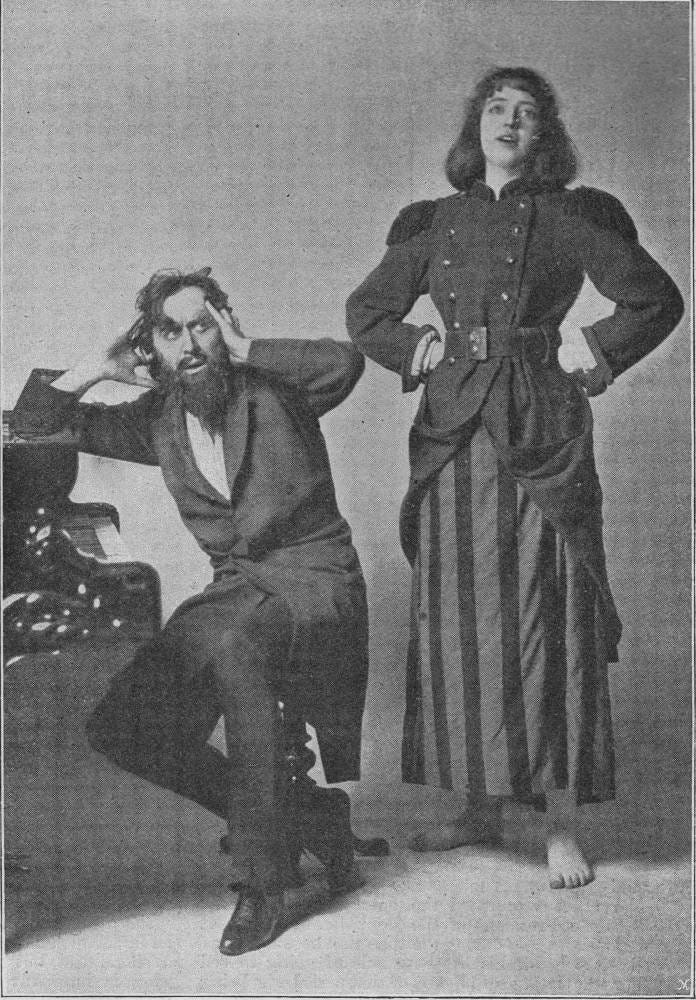

Literary Events are nothing new, of course. I’m sure you know the (probably apocryphal) stories about the American crowds who stormed the docks of New York City for the latest installment of Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop, anxious to learn the fate of Little Nell. Research on my current book has led me to learn more about the du Maurier family; their patriarch and granddad of Daphne, George du Maurier, wrote the serial novel Trilby, which was such a sensation at the end of the 19th century influenced everything from hats to feet (I kid you not) and gave us the idea of the Svengali. Today, serialized TV2 has somewhat replaced the fervor that these serialized books once generated, but new drops in huge book series still have the ability to give us the thrill of, say, a reader in 1852 encountering a new chapter of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the National Era.

What’s interesting to me about Sally Rooney books as Literary Events is that they are so very insular as texts. The worlds they create are claustrophobic; a close literary equivalent may be the “little bit (only two inches wide) of ivory” upon which Jane Austen famously worked. Austen wrote this phrase in a letter to her nephew, comparing (with typical Jane-ish sneer) comparing the “strong, manly, spirited sketches” written by him to her own novels.3 The gendering here is important; Austen’s creation of miniature paintings on ivory is feminine work. Yet it is not deprecating or coy. Austen knew a miniature contains a whole world, and perhaps more skill is involved in creating it than in a large canvas.

Like Austen, Rooney finds whole worlds in a single look, a word, an action or an inaction. The miniature worlds she builds—which exist as a set of relations between lovers, between brothers, between her books and her readers—leave me breathless as a reader. It’s never taken me longer than three or four days to finish a Rooney novel. Like swimming in very cold water, you immerse yourself and are immediately consumed with the world, perhaps uncomfortably so. Of course, that’s part of the point. Rooney doesn’t write characters that are easy to love. In Intermezzo, she comes closer than ever before in the central dyad of brothers Ivan and Peter. Ivan’s the chess player; Peter’s a successful barrister. Both are reeling from the recent death of their father. Rooney splits the point-of-view between the brothers, giving Peter a breathless, subjectless way of narrating that feels like a racing heart. Ivan, the younger brother, is easier to like (and easier to read). They’re hurting with grief, and lashing out at each other, and dealing with romantic troubles. But the close narration forces you into their brains and makes you root for them.

Like Jane Austen’s works, Sally Rooney’s claustrophobic books can be seen as reflections on the constraints (two inches wide) of the novel itself. In an interview, Rooney said of the novel,

Yes, you have to feel hemmed in by its limitations to truly love it, to feel excited by it. I like the limitations of the novel. I like feeling them pressing in on me while I’m trying to get close to my characters.

As a reader, Rooney’s first two novels evidence the form closing in on the writer in a sort of anxious adrenaline that fizzes over and ultimately leaves a reader feeling empty. I read Normal People first, then Conversations With Friends. I finished both in a day or two, absorbed to the point of nervous claustrophobia with these characters, none of whom I really liked all that much, and their feelings.

Maybe the anxiety was the point of the books, but as an audience for the artistic production, I much preferred the TV adaptation of Normal People; somehow losing the closely narrated inner lives of Connell and Marianne made them much more palatable protagonists. Hiring Paul Mescal and Daisy Edgar-Jones to play the characters probably didn’t hurt, nor did the TV show’s release corresponding exactly with the early months of the pandemic. To say I loved Normal People is an understatement. I sang about it from the rooftops!

Intermezzo achieves something close to what the adaptation of Normal People did; it offers a sincerity that feels like a tonic in these troubled times. Like Fanny Price in Mansfield Park or Anne Elliot in Persuasion, there is an essential goodness to these characters and an essential belief in the ways that human relationships can save us. Maybe an even better comparison is between Ivan and Peter and Elinor and Marianne in Sense and Sensibility, pairs of chalk-and-cheese grieving siblings who struggle mightily with each other and with the forces beyond, but who ultimately learn to stop struggling and forgive.

Forgiveness takes time, and so do good novels. I think this is Rooney’s best, and I think it deserves time. Intermezzo may be an “INSTANT NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER,” as its Amazon landing page proclaims (how does the timing of that even work? buying books to make them bestsellers takes time!), but it is also a novel that will be waiting for you whenever you are ready for it—today, tomorrow, in ten years’ time. The best books always do.

Thanks for reading The Booklight. I’ll be back in two weeks with more thoughts on bookish topics, publishing, and culture. Until then, Jill. xo

Though I can’t help but note the juxtaposition of all that Intermezzo swag with Rooney’s own anti-consumerist, anti-capitalist stance. In the Paris Review interview, she says, “What I would like to develop is an aesthetics of anti-consumerism, an aesthetics that is against buying and that can resist the extreme weight of the capitalist content-production mill. I want to play whatever tiny, grain-of-sand role I can in developing that aesthetic program, in making something beautiful that says no to consumerism, disposability, endless growth, and that is consonant with a political project, even if it’s not in itself political.” BUT WHAT ABOUT THE TOTE BAGS?!

Where are my fellow Severance fans at?